Executive Summary

As courts, Congress, the Department of Justice, and the Federal Trade Commission consider foundational issues of antitrust law and enforcement, states should take this opportunity to reassess their role in the antitrust ecosystem. Over the years, states have filed significant antitrust lawsuits, on their own and in conjunction with federal agencies. Today, states are bringing several substantial lawsuits against the nation’s largest technology companies that, if successful, could reorder the entire industry. All this activity, however, leaves open the question of whether states should play a leading role in antitrust enforcement. Are the states winning in court? Are their lawsuits helping consumers? How much value can states add when both the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice have divisions dedicated to antitrust enforcement?

This review of cases and leading commentaries shows that states should focus their involvement in antitrust cases on instances where:

- they have unique interests, such as local price-fixing

- play a unique role, such as where they can develop evidence about how alleged anticompetitive behavior uniquely affects local markets

- they can bring additional resources to bear on existing federal litigation.

States can also provide a useful check on overly aggressive federal enforcement by providing courts with a traditional perspective on antitrust law — a role that could become even more important as federal agencies aggressively seek to expand their powers. All of these are important roles for states to play in antitrust enforcement, and translate into positive outcomes that directly benefit consumers.

Conversely, when states bring significant, novel antitrust lawsuits on their own, they don’t tend to benefit either consumers or constituents. These novel cases often move resources away from where they might be used more effectively, and states usually lose (as with the recent dismissal with prejudice of a state case against Facebook). Through more strategic antitrust engagement, with a focus on what states can do well and where they can make a positive difference in antitrust enforcement, states would best serve the interests of their consumers, constituents, and taxpayers.

Introduction

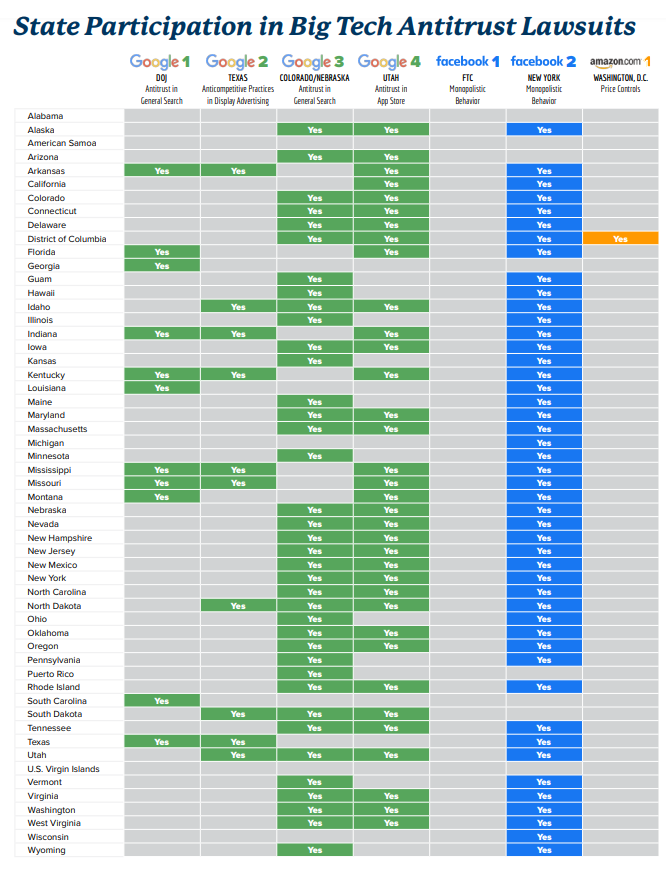

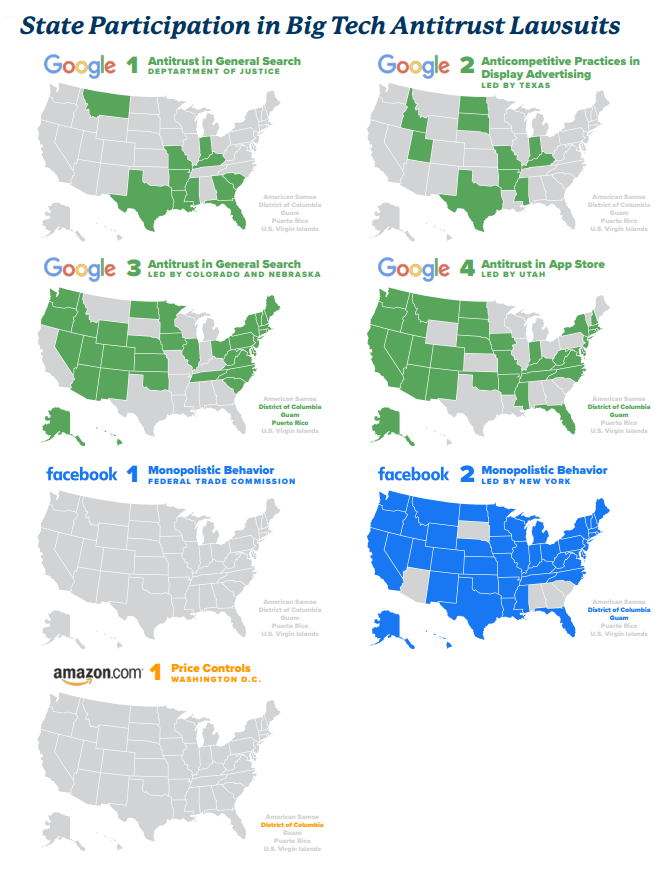

For the first time in decades, antitrust is front and center in the national discourse. Four government lawsuits on antitrust grounds are pending against Google, two against Facebook, and one against Amazon. Other government and private antitrust cases against large technology companies are in the pipeline.1See., e.g., David McLaughlin, “U.S. DOJ Readying Google Antitrust Lawsuit Over Ad-Tech Business,” Yahoo! Finance, September 1, 2021, available at: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/u-doj-readying-google-antitrust-204728728.html Prominent members of Congress from both parties have proposed bills to rewrite the antitrust laws. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC)’s new Chair, Lina Khan, has advocated for antitrust rulemakings, rescinded a 2015 antitrust policy statement that set parameters for the types of cases the FTC will bring, and recently rescinded its Vertical Merger Guidelines.2U.S. Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Rescinds 2015 Policy that Limited Its Enforcement Ability Under the FTC Act,” July 1, 2021, available at: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2021/07/ftc-rescinds-2015-policy-limited-its-enforcement-ability-under; U.S. Federal Trade Commission, “Federal Trade Commission Withdraws Vertical Merger Guidelines and Commentary,” September 15, 2021, available at: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2021/09/federaltrade-commission-withdraws-vertical-merger-guidelines These actions raise many questions about the future of federal antitrust law and enforcement.

Amidst this activity, few have examined the role of the states in the antitrust ecosystem, even though most state attorneys general play a significant role in recent key lawsuits. Of the seven current governmental lawsuits against the Big Tech companies, five are led by state attorneys general, with the FTC and Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division (DOJ) each leading the others. These cases raise important questions about venue, consolidation and choice of law. Should states go it alone in bringing cases with broad, national implications and importance? Facebook, Google, Amazon, and most other large tech firms serve residents of all 50 states.

With successful antitrust lawsuits, a few states could disrupt the entire industry and affect consumers across the country. Should the Texas Attorney General’s decisions about which antitrust cases to bring affect how those companies operate in Illinois? Or should such interstate cases be left to the federal government? What if a state adopts antitrust laws that differ sharply from federal law? New York’s legislature is considering a bill that would replace the venerable consumer welfare standard with a looser standard that invites a return to more politicized antitrust enforcement that does not require enforcers to show that the conduct by companies actually causes harm to consumers.3New York State Assembly, “Twenty-First Century Anti-Trust Act,” Bill No. S00933A, introduced January 6, 2021, available at: https://nyassembly.gov/leg/default_fld=&leg_video=&bn=S00933&term=&Summary=Y&Text=Y

Given the size of New York’s market, would New York suddenly dictate antitrust standards to the rest of the country, including the federal government? This paper will reexamine the role of state antitrust enforcement and evaluate the critique originally set forth by former Judge Richard Posner, for decades one of the nation’s leading antitrust scholars. In a seminal article, Posner cautioned against heavy state involvement in antitrust cases on grounds that states cannot match federal resources, that states tend to submit briefs and arguments of lower quality than federal agencies, and that political considerations may have an outsized effect in state enforcement decisions.4Richard A. Posner, Antitrust in the New Economy, 68 Antitrust Law Journal 925, at 940-941 (2001)

This paper will consider two additional concerns. First, state antitrust enforcement may be more politicized, leading to cases which are not in the best interest of consumers. Second, a high number of states that can bring lawsuits against a single company, which could end up forcing companies to settle rather than face expensive legal action, even in absence of consumer harm. Or these companies may give in to the pressure created by public scrutiny to force settlements that may not be in the best interest of consumers. This is especially possible if cases are brought against different parts of a company and cases are not consolidated into a single venue.

We conclude that, while we do not entirely agree with Judge Posner, he raises an important cautionary alarm. Recent state enforcement has not been particularly effective, especially when states go it alone without access to the investigatory resources and expertise of the federal agencies.

More importantly, overly aggressive state antitrust enforcement can undermine consumer welfare in favor of regional economic interests or short-term political outcomes.

Accordingly, instead of bringing complex, novel antitrust cases of national import on their own, states should focus their antitrust involvement on instances where they have unique interests, can play a unique role, or can supplement federal resources in existing litigation. States can also provide a useful check on overly aggressive federal enforcement by providing courts with a traditional perspective on antitrust law — a role that could become even more important as federal agencies aggressively seek to expand their powers. Through such strategic engagement, states would best serve the interests of their consumers, constituents, and taxpayers.

This Paper Will Examine These Concerns:

the role of state antitrust enforcement and evaluate the critique

state antitrust enforcement may be more politicized, leading to cases which are not in the best interest of consumers

a high number of states that can bring lawsuits against a single company, which could end up forcing companies to settle rather than face expensive legal action, even in absence of consumer harm

Background on Antitrust Standards and Current Debate

The state and federal governments share overlapping antitrust jurisdiction and enforce antitrust laws through a federalist balance. Individuals and corporations can also bring private antitrust suits.

Federal antitrust laws date back to the Sherman Act, passed in 1890; and the Clayton Act and the Federal Trade Commission Act, passed in 1914. These statutes remain the major federal enforcement mechanisms. In the federal government, the Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Competition (FTC) are the primary enforcement agencies. For the most part, the DOJ and FTC have overlapping authority, though only the DOJ can bring criminal antitrust cases. Over time, the DOJ and FTC have worked out ways of allocating cases, largely based on their expertise and past experience in particular industries or markets.5The FTC website explains the relationship between FTC and DOJ enforcement in more detail in “The Enforcers,” Federal Trade Commission, visited September 3, 2021, available at: https://www.ftc.gov/tips-advice/competition-guidance/guideantitrust-laws/enforcers For instance, the DOJ tends to take the lead in aerospace and defense mergers, whereas the FTC often takes the lead on health care issues.6At one point in time, the agencies actually worked out a formal clearance agreement, but that has lapsed. See U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, “Memorandum of Agreement Between the Federal Trade Commission and the Antitrust Division of the United States Department of Justice Concerning the Clearance Procedures for Investigations,” July 17, 2007, available at: https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2007/07/17/10170.pdf Some other federal agencies, such as the Federal Communications Commission, also play a limited role in antitrust enforcement.7For example, the Federal Communications Commission has authority to approve license transfers for broadcasters and often bases its decisions to approve such transfers on antitrust considerations, among other considerations. See., e.g., Brent Skorup and Christopher Koopman, “The FCC’s Transaction Reviews and First Amendment Risks,” Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, Vol. 39, No. 3, 2016, available at: https://www.harvard-jlpp.com/wp-content/uploads/ sites/21/2016/06/39_3_Skorup-Koopman_F.pdf

Today, federal courts (and many state courts) base antitrust decisions on the “consumer welfare standard.”8California is a prominent example of a state whose antitrust statute and judicial interpretations of that statute have not followed the consumer welfare standard and have instead protected the interests of certain favored businesses at the expense of consumer welfare. See, e.g., Timothy Sandefur, “Discussing State-Level Antitrust Enforcement with the Alliance on Antitrust, November 20, 2020, available at: https://sandefur.typepad.com/freespace/2020/11/discussing-state-level-antitrustenforcement-with-the-alliance-on-antitrust.html This is an economic test which focuses on a cost/ benefit analysis for consumers, based on the prices they pay, quality of products or services, and other criteria that can be turned into an economic calculation. If the costs to consumers outweigh the benefits, the conduct may be considered anticompetitive and in violation of the antitrust standards.

Consumer welfare is often misunderstood as simply policies that favor consumers over producers. Instead it’s better understood as efficient allocation of economic resources that benefit both consumers and the economy as a whole. As Judge Bork writes in the Antitrust Paradox “… and the distribution of resources would be ideal. Output, as measured by consumer valuation would then be maximized since there would be no possible rearrangement of resources that could increase the value to consumers of the economy’s total output.”9Robert H. Bork, The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself, 1978, 2021, p. 97.

Courts did not always follow the consumer welfare standard. Early cases were generally based on subjective criteria. For example, in one of the first cases to interpret the Sherman Act, the Supreme Court said that it was basing its decision on protecting “small dealers and worthy men.”10United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Ass’n, 66 U.S. 290, at 323 (1897). This decision seemed to simply reflect the philosophical preferences of the Supreme Court at that time rather than some kind of objective standard that could be relied upon in future cases. What this meant for consumers is unclear, and over the decades that followed, antitrust enforcement was unpredictable and often ideologically motivated.

The Justice Department’s successful challenge of a merger of two relatively small Los Angeles grocery chains in the 1960s illustrates how far antitrust enforcement went before the consumer welfare standard. By the DOJ’s own evidence, that merger would have accounted for only 7.5% of the market. The Justice Department provided a very shallow analysis and claimed that the merger would be a step toward creating market dominance by a small number of grocery store chains in the future. The government prevailed despite evidence that entry was not difficult and the market was becoming less concentrated.11United States v. Von’s Grocery Co., 384 U.S. 270 (1966). Justice Potter Stewart’s famous dissenting opinion pointed out the lack of economic foundation for the decision in this and other antitrust cases before the Court: “The sole consistency that I can find is that in litigation under Section 7 (merger enforcement), the government always wins.”12United States v. Von’s Grocery Co., 384 U.S. 270, 301 (1966) (Stewart & Harlan, JJ, dissenting).

By the end of the 1970s, the Supreme Court recognized the need for consistency when evaluating whether business conduct violates the antitrust laws, and settled on the consumer welfare standard. In the 1977 decision of Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania, Inc., regarding territorial restraints on franchisees, the Court held that rule of reason antitrust standards must be based upon demonstrable economic effect.13Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc, 433 U.S. 36, at 58-59 (1977). The Supreme Court reaffirmed this need for applying a firm economic foundation for antitrust analysis in 2015, even when it meant reversing precedent from before the consumer welfare standard. As Justice Kagan wrote for the majority:

Congress, we have explained, intended that law’s reference to “restraint of trade” to have “changing content” and authorized courts to oversee the term’s “dynamic potential.” We have therefore felt relatively free to revise our legal analysis as economic understanding evolves and . . . to reverse antitrust precedents that misperceived a practice’s competitive consequences. Moreover, because the question in those cases was whether the challenged activity restrained trade, the Court’s ruling necessarily turned on its understanding of economics.

A recent article by scholars associated with the International Center for Law and Economics explains the importance of maintaining the consumer welfare standard:

Today, the consumer welfare standard offers a rigorous, objective, and evidence-based framework for antitrust analysis. It leverages developments in modern economics more reliably to predict when conduct is likely to harm consumers as a result of harm to competition. It offers a tractable test that is broad enough to contemplate a variety of evidence related to consumer welfare but also sufficiently objective and clear to cabin discretion and honor the principle of the rule of law. Perhaps most significantly, it is inherently an economic approach to antitrust that benefits from new economic learning and is capable of evaluating an evolving set of commercial practices and business models. These virtues are precisely the target of the new populist antitrust movement, which seeks to reject economics in favor of mere supposition.1Elyse Dorsey, Geoffrey A. Manne, Jan M. Rybnicek, Kristian Stout, and Joshua D. Wright Consumer Welfare & the Rule of Law: The Case Against the New Populist Antitrust Movement, 47 Pepp. L. Rev. 861 (2020), at 862, available at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/plr/vol47/iss4/1

As evidenced by Justice Kagan’s opinion, the consumer welfare standard isn’t just a standard of one legal ideology, it is the standard courts look to for antitrust guidance. But this mindset may be changing.

Many legal scholars, intellectuals and political figures have harkened back to a pre-consumer welfare understanding of antitrust often known as “Neo-Brandeisian” or “hipster” antitrust. Rather than focusing exclusively on consumer welfare, they suggest antitrust laws can be used to a number of other ends such as promoting free speech, addressing wage inequality, and even social justice.14For brief surveys of the Neo_Brandeisian school and some of its claims, see, e.g., Andrea O’Sullivan, “What is ‘Hipster Antitrust?’” The Bridge, October 18, 2018, available at https://www.mercatus.org/bridge/commentary/what-hipster-antitrust; David Dayen, “This Budding Movement Wants to Smash Monopolies,” The Nation, April 4, 2017, available at https://www.thenation.com/article/this-budding-movement-wants-to-smash-monopolies/ The current chair of the FTC, Lina Khan, identifies with neo-Brandeisian views, including in a recent memo to FTC staff stating that she wants to focus antitrust enforcement on helping workers and preserving independent business.15Lina Khan, “Memo from Chair Lina M. Khan to Commission Staff and Commissioners Regarding the Vision and Priorities for the FTC,” September 29, 2021, available at: https://www.ftc.gov/public-statements/2021/09/memo-chair-lina-m-khan-commission-staff-commissioners-regarding-vision These goals echo the “small dealers and worthy men” previously the beneficiaries of antitrust law. For many, the cases filed against the large tech companies are a battleground between these competing ideologies.

As we discuss below, some of the current proposals for more activist antitrust enforcement are Neo-Brandeisian in nature. Untethering antitrust enforcement from the consumer welfare standard raises concerns about a return to the past of antitrust enforcement where an antitrust violation was anything the government said was an antitrust violation, regardless of the impact on competition, economic efficiency or the net impact on the economy. Moving away from the consumer welfare standard invites politicized enforcement as government appointees and judges pick winners and losers by whatever criteria they choose to apply.

State Antitrust Laws and Enforcement

States have their own antitrust laws—indeed, some states had enacted antitrust laws before the Sherman Act.16Throughout this paper, the terms “state” and “state attorney general” are used somewhat loosely to include the District of Columbia, the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and the territories of American Samoa, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, as well as their respective attorneys general Mirroring the federal statutes, state laws tend to prohibit anticompetitive conduct in broad terms, but some states also have laws prohibiting certain conduct in specific industries, such as alcoholic beverages, dairy products, and motor fuels. Two states, Connecticut and Washington, require premerger notification to state authorities of certain health care mergers.17Attorney General for the State of New York, “Antitrust Enforcement, visited September 3, 2021, available at: https://ag.ny.gov/antitrust/antitrust-enforcement These state laws generally operate in tandem with federal law, without federal preemption, even when there are some differences. States’ antitrust authority is independent of the federal government; states may bring their own antitrust cases even if the DOJ or FTC choose not to pursue antitrust claims.18The most notable difference between state and federal law regards indirect purchasers. As a result of a Supreme Court decision, under federal law, antitrust damages cannot be recovered by an indirect purchaser, such as someone who bought from a middleman who previously bought from the company that violated an antitrust law. Illinois Brick Co. v. Illinois, 431 U.S. 270 (1977). In other words, only the party who bought directly from the seller who violated an antitrust law can recover damages. In reaction to that court decision, many states allowed indirect purchasers to have standing to sue and recover damages.

In terms of enforcement, states can give their attorneys general broad powers to investigate conduct for antitrust violations that arise under state law. States took on a larger role in enforcing federal antitrust law in the 1970s, when Congress passed the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act (HSR Act).19Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976, 15 U.SC. Section 15. Part of the Congressional motivation for passing the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act was the judicial rejection of California’s lawsuit to sue as parens patriae for damages on behalf of its citizens in California v. Frito-Lay, 474 F.2d 474 (9th Cir. 1973) The HSR Act authorized state attorneys general to bring antitrust suits either on behalf of individuals residing within their states, known as parens patriae suits, or on behalf of the state as a purchaser. Under this statute, states can seek treble damages and request injunctive relief for Sherman Act violations where the damages are suffered by natural persons (i.e., not by corporations, LLCs, or partnerships), though the victims must be given an opportunity to opt out and bring their own private antitrust lawsuit.20Private parties can also bring suits to enforce the federal antitrust laws and seek recovery for damages that they suffered due to antitrust violations. Some state antitrust laws also authorize antitrust suits by individuals. In most years, antitrust lawsuits by private parties far outnumber those brought by governments, although private claims tend to seek much smaller damages amounts. Congress further encouraged state antitrust enforcement through the Crime Control Act of 1976, which included seed money to state attorneys general to create their own antitrust sections.21Crime Control Act of 1976, Public Law 94-503. As a result of these statutory schemes, states can bring antitrust enforcement actions under both federal law and their own state antitrust laws. For instance, New York’s attorney general can enforce federal antitrust law or New York’s antitrust law, called the Donnelly Act, which closely parallels the Sherman Act in that it prohibits price fixing, bid rigging, and other practices commonly understood to violate federal antitrust law.22See Attorney General for the State of New York, “Antitrust Enforcement,” visited September 3, 2021, available at: https://ag.ny.gov/antitrust/antitrust-enforcement Still, states often choose to bring federal parens patriae claims rather than pursue the same claims under their state laws, perhaps because federal law provides a robust body of case law to guide courts and litigants. Almost all of the current cases brought by states against tech companies, with the exception of the case by the District of Columbia, are federal parens patriae claims.

Despite their activity, states have limited antitrust resources compared to the federal agencies. As a result, the most significant state enforcement actions are almost always brought in coalition with other states, and often the federal agencies. In 1983, the National Association of Attorneys General formed its Multistate Antitrust Task Force, which is now the main mechanism for coordinating multistate antitrust litigation. The Task Force has issued various guidelines, protocols, and policy statements to address the manner in which states analyze antitrust concerns and work together.23For more information on the Multistate Antitrust Task Force, including copies of litigation documents and policy statements, see National Association of Attorneys General, “Antitrust,” available at: https://www.naag.org/issues/antitrust/ Recently, states have called on Congress to renew funding for their attorneys general to enforce antitrust laws.24National Association of Attorneys General, “Bipartisan Coalition of Attorneys General Call on Congress to Support Federal Funds for State Antitrust Enforcement, press release, May 21, 2021, available at: https://www.naag.org/press-releases/bipartisan-coalition-of-attorneys-general-call-on-congress-tosupport-federal-funds-for-state-antitrust-enforcement/

The Sherman Act, which is used to enforce antitrust law, goes back to 1890. Back then, It was unclear how courts should interpret the language of the law.

Today, courts base decisions in antitrust law around the consumer welfare standard.

The standard provides an objective and evidence-based framework to evaluate antitrust cases and see if consumers would be harmed or benefited by a court interfering with the market.

States can bring laws under both state and federal antitrust laws.

Most enforcement action at the state level is brought via a state coalition.

Recent State Involvement in Significant Antitrust Cases

State attorneys general have played a role in many significant antitrust cases, with mixed results. A brief review of these cases shows that states can effectively supplement federal resources and serve as a check on overly aggressive federal enforcement, but they usually fail when they act more aggressively than the federal agencies.

United States v Microsoft Corp. (1998)

No case is more relevant to the concerns about large technology companies than the Microsoft case of the 1990s and 2000s. Concerns abounded in institutions and in the press about the size and dominance of Microsoft. Although concerns varied, the largest was that Microsoft would control access to the internet through its Windows platform and Internet Explorer program. It could then act as a gatekeeper and extract rent for online transactions and expand into adjacent markets.

In its seminal antitrust case against Microsoft, the Department of Justice was joined by 20 other states and the District of Columbia. New York’s attorney general in particular played a leading role in the litigation that likely supplemented the DOJ’s resources. The complaint claimed that Microsoft illegally leveraged its dominant market position in personal computer operating systems to prevent manufacturers from uninstalling Internet Explorer. It also claimed that it took actions to disfavor competing software such as an alternative browser known as Netscape and the programming language Java.25While Java was not a browser, it removed the operating system from the software development equation. This allowed programs written in Java to work on any operating system. Microsoft wanted to prevent this from happening to make sure software only worked well on its Window’s operating system. The authorities won at trial (which would have required a breakup of the company), but the relief was mostly reversed on appeal.

In 2001, the DOJ reached a settlement with Microsoft that required the company to share certain application programming interfaces (API) with third-party companies and to appoint a compliance panel to oversee the process for five years. This would allow the competitors to Internet Explorer to better integrate on Windows software. But 10 state attorneys general (not including New York’s) challenged the settlement, claiming it was insufficient.26The 9 states objecting to the settlement with Microsoft were California, Connecticut, Iowa, Florida, Kansas, Massachusetts, Utah, and Virginia, along with the District of Columbia. Their challenge delayed but did not change the outcome, and the settlement was approved by the appellate court three years later.27United States v. Microsoft Corp., 87 F. 87 F. Supp 2d 30 (D.D.C. 2000); 97 F. Supp 2d 59 (D.D.C. 2000), direct appeal denied, pet. cert. denied, 510 U.S. 1301 (2000); Microsoft Corp. v. United States, 534 U.S. 952 (2001) (pet. cert. denied); 224 F. Supp 2d 76 (D.D.C. 2002); 231 F. Supp. 2d 144 (D.D.C. 2002) (on remand), aff’d in part and rev’d in part, 373 F.3d 1199 (D.C. Cir. 2004).

It’s hard to quantify the impact of the case on the market. While Netscape ultimately did not win market share in the browser industry, it’s possible the settlement allowed for the growth of competitors such as Mozilla Firefox and Google Chrome, which ultimately took much of Microsoft’s market share. On the other hand, personal computers are not the gateway to the internet they once were. Mobile devices now generate the majority of web traffic, much of which funnels through applications rather than a browser, so innovation may have solved the issue regardless of the court’s remedy.

In a 2019 interview, Bill Gates claimed that the antitrust suit may have hurt competition in the mobile industry, saying “there’s no doubt the antitrust lawsuit was bad for Microsoft, and we would have been more focused on creating the phone operating system, and so instead of using Android today, you would be using Windows Mobile if it hadn’t been for the antitrust case.”28Jordan Novet, “Bill Gates Says People Would Be Using Windows Mobile If Not for the Microsoft Antitrust Case,” CNBC, November 6, 2019, available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/06/bill-gates-people-would-use-windows-mobile-if-not-for-antitrust-case.html Perhaps there would be a third major mobile operating system if the Microsoft case had not been drawn out so long or made Microsoft hesitant to invest in new sectors.29Or perhaps the suits are an excuse for Microsoft’s failure to lead in these categories.

Ohio v. American Express (2018)

More recently, the states lost another important case when they acted more aggressively than the federal government. Most domestic credit cards are issued by Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover. Discover charges merchants less for transactions than the other card issuers, giving merchants an incentive to encourage customers to use Discover cards instead of the competing cards. In response, Visa, Mastercard and American Express imposed “anti-steering” provisions in their agreements with merchants that prohibited them from steering customers to use other cards.

The DOJ, joined by 17 states, sued Visa, Mastercard, and American Express, claiming that their anti-steering contract provisions led to merchants charging higher prices to customers to make up for the higher fees for their credit cards.30The 17 states joining the DOJ lawsuit were Arizona, Connecticut, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, New Hampshire, Montana, Nebraska, Ohio, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, Utah, and Texas. At one point, Hawaii joined the DOJ lawsuit, but then withdrew its claims before the trial began. Visa and Mastercard settled their case before trial by agreeing to drop the anti-steering contact language. American Express, however, refused to settle. The DOJ-led plaintiffs won at the trial court, but lost on appeal.

The DOJ then dropped the case, but 11 states, with Ohio taking the lead, appealed to the Supreme Court. 31The 10 states joining Ohio in the appeal to the Supreme Court were Connecticut, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Montana, Rhode Island, Utah and Vermont. Rejecting the states’ arguments, the Court held that the states failed to show any harm specific to the anti-steering provisions or that there was any loss of competition among credit card issuers due to these provisions.32United States v. Am. Express Co., 88 F. Supp 3d 143 (E.D.N.Y 2015); reversed, 838 F.3d 179 (2d Cir. 2016); cert. granted, 138 S. Ct. 355 (2017), 138 S. Ct. 2274 (2018)

Merger of T-Mobile and Sprint (2019)

As another recent example, in 2019, the DOJ and five states reached a settlement with T-Mobile and Sprint to approve their merger of competing cellular services, subject to certain divestitures.33U.S. Department of Justice, “Justice Department Settles with T-Mobile and Sprint in Their Proposed Merger by Requiring a Package of Divestitures to Dish,” July 26, 2019, available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-settles-t-mobile-and-sprint-theirproposed-merger-requiring-package This merger combined the nation’s third- and fourth-largest cellular providers, but the combined company was still smaller than AT&T and Verizon. The merging parties argued that a combined company would create a stronger competitor with a greater ability to build out a 5G network.

Despite the settlement, New York led 12 other states and the District of Columbia to file their own merger challenge.34The other 12 states besides New York seeking to block the merger were California, Connecticut, Colorado, Hawaii, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Nevada, Virginia, and Wisconsin, along with the District of Columbia. They argued that the merger harmed consumers because it reduced the number of major cellular providers from four to three. This was a particularly difficult challenge because of the merger’s complexity and because the states had to develop their facts and arguments without the DOJ’s support. Perhaps not surprisingly, the trial court rejected the challenge, finding little evidence of harm to consumers. Instead, it determined that the combined company’s resources would likely improve competition.35U.S. Department of Justice, “Justice Department Settles with T-Mobile and Sprint in Their Proposed Merger by Requiring a Package of Divestitures to Dish,” Press Release, July 26, 2019, available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-departmentsettles-t-mobile-and-sprint-their-proposed-merger-requiring-package; State of New York et al v. Deutsche Telekom AG et al, No. 1:2019cv05434 – Document 409 (S.D.N.Y. 2020), available at: https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/new-york/nysdce/1:2019cv05434/517350/409/. [19] For a more complete discussion of the AT&T/Time Warner merger litigation and the later plans by AT&T to sell DirecTV, see Theodore R. Bolema, “Lessons from the Department of Justice v. AT&T: The Difficulty of Predicting Outcomes in Dynamic Markets,” Perspectives from FSF Scholars, Vol. 15, No. 48 (September 16, 2020), available at: https://freestatefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Lessons-from-the-Department-of-Justice-v.-ATT-%E2%80%93-The-Difficultyof-Predicting-Market-Outcomes-in-Dynamic-Markets-091620.pdf; Theodore R. Bolema, “The Proper Context for Assessing the AT&T/ Time Warner Merger,” Perspectives from FSF Scholars, Vol. 13, No. 6 (February 8, 2018), available at: https://freestatefoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/The-ProperContext-for-Assessing-the-ATT-Time-Warner-Merger-020818.pdf

Merger of AT&T and Time Warner (2019)

On the other hand, the states sometimes act as a valuable check on the federal agencies. In 2017, the DOJ challenged the proposed vertical merger of AT&T and Time Warner. At the time of the merger, AT&T was a major programming distributor through its DirecTV and U-Verse services. Time Warner was primarily a media and entertainment content provider, owning CNN, HBO, Turner Broadcasting System and Warner Brothers. Several years earlier, Time Warner had sold off its cable operations, so at the time of the merger, the two companies did not directly compete in any significant way. Antitrust agencies rarely challenge this type of vertical merger, which most observers find generally pro-competitive.36U.S. Department of Justice, “Vertical Merger Guidelines,” June 30, 2020, available at: https://www.justice.gov/atr/page/file/1290686/download

At least 20 state attorneys general joined the DOJ to actively investigate the merger.37Diane Bartz and David Shepardson, “U.S. Government Approaches 18 States to Fight AT&T-Time Warner Deal,” Reuters, November 20, 2017, available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-time-warner-m-a/u-s-government-approaches-18-states-to-fight-att-timewarner-deal-idUSKBN1DF25Q But in the end, none of them chose to join the DOJ’s lawsuit, which lost both at the trial court and on appeal. Indeed, nine states filed an amicus brief opposing the DOJ’s appeal.38David Shepardson, “Nine State Attorneys General Back AT&T in Time Warner Appeal, Reuters, September 26, 2018, available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-time-warner-m-a-t-t/nine-state-attorneys-general-back-att-in-time-warner-appeal-idUSKCN1M6373 The states highlighted the unusually aggressive nature of the DOJ’s arguments. As they pointed out, it “is rare for the federal government to pursue an antitrust case involving major, national companies without any state joining the effort.” In this case, the state attorneys general had better antitrust judgment than the DOJ, and their amicus brief may have helped to undermine the lawsuit’s credibility before the court.39Interestingly, the finding by the trial court of a lack of evidence of any anticompetitive harm was further confirmed in early 2021, when AT&T sold off DirecTV, the very business unit that DOJ alleged would benefit in an anticompetitive way from the merger.

Lessons from the Cases

As this brief review shows, state attorneys general can effectively supplement federal resources and serve as a check on overly aggressive federal enforcement. They can assist the DOJ and FTC through their own expertise, manpower, and credibility. On the other hand, states typically fail when they act more aggressively than their federal counterparts. The federal agencies have every incentive to develop and bring meritorious cases, and they also have readier access to experienced antitrust lawyers, economists and econometricians. For these reasons, in complex and novel cases, the states are unlikely to find winning lawsuits or arguments where the feds have already examined the issues and taken a pass. These cases hold lessons for states’ ongoing and future antitrust enforcement, including the pending lawsuits against Facebook, Amazon, and Alphabet (the parent company of Google).

States and Big Tech Litigation

Most of the current attention in antitrust is focused on the government lawsuits against the previously mentioned large technology companies. While this paper cannot examine the ins and outs of each case, it will discuss the main arguments and the states’ involvement. The appendix includes a list of the plaintiff federal agencies and attorneys general.

To date, Federal Trade Commission v. Facebook and New York v. Facebook are the only cases to have had rulings on the merits. Both were heard by Judge James E. Boasberg in federal district court in the District of Columbia.

In its initial complaint, the FTC argued that Facebook’s website and mobile app, described in the complaint as “Facebook Blue,” held a monopoly over “personal social networking services.” The FTC sought a “permanent injunction in federal court that could, among other things: require divestitures of assets, including Instagram and WhatsApp; prohibit Facebook from imposing anticompetitive conditions on software developers; and require Facebook to seek prior notice and approval for future mergers and acquisitions.”

The state case, led by New York on behalf of 48 states, alleged similar violations and sought similar relief.

The lawsuits hinged on two key claims: that Facebook purchased Instagram and WhatsApp to protect against potential competitors and that Facebook holds a monopoly with sixty percent of the Personal Social Networking Market (as defined by the government) and has done so since 2011.

Similar to the DOJ’s lawsuit against AT&T and TimeWarner, these lawsuits advanced several very aggressive theories. For one thing, the suits sought to unwind Facebook’s acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp almost a decade after those mergers had been consummated, an unusual if not entirely unprecedented move. For another, the suits pursued a “nascent competition” theory that Instagram and WhatsApp, had they not been purchased by Facebook, eventually would have grown to become horizontal competitors to Facebook, even though they weren’t at the time Facebook acquired them.

The court dismissed both lawsuits. For the FTC’s complaint, the court found that the FTC had failed to plead sufficient facts showing that Facebook had a monopoly at all: the “Complaint contains nothing on that score save the naked allegation that the company has had and still has a “dominant share of th[at] market (in excess of 60%).”40FTC v. Facebook, Inc., Memorandum Opinion, U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, June 28, 2021, Civil Action No. 20-3590 (JEB), available at: https://s.wsj.net/public/resources/documents/facebook0628.pdf

To date, the FTC has filed an amended complaint,41Federal Trade Commission v. Facebook, Inc., First Amended Complaint, No. 20-3590 (JEB) (D.D.C. June 28, 2021), available at: https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.224921/gov.uscourts.dcd.224921.73.0.pdf which largely mirrors the initial complaint, but also suggests that Snapchat is Facebook’s competitor in personal social networking. According to the FTC, companies like Twitter, Reddit, LinkedIn, and Pinterest, are not competitors since they do not provide the same features. Likewise, the FTC asserts that TikTok is not a substitute because “TikTok users primarily view, create, and share video content to an audience that the poster does not personally know, rather than connect and personally engage with friends and family.” Time will tell whether the FTC’s proposed market definition survives scrutiny.

The court also dismissed the states’ suit, with prejudice. The court found that they had waited too long to bring it, given that Facebook had acquired Instagram and WhatsApp years previously, in 2012 and 2014: “The Court is aware of no case, and Plaintiffs provide none, where such a long delay in seeking such a consequential remedy has been countenanced in a case brought by a plaintiff other than the federal government, against which laches [the delay doctrine] does not apply and to which the federal antitrust laws grant unique authority as sovereign law enforcer.”42State of New York, et al., Facebook, Inc., Memorandum Opinion, Civil Action No. 20-3589 (JEB)(D.D.C. June 28, 2021),, available at: https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.224923/gov.uscourts.dcd.224923.137.0.pdf On July 28th of 2021, the attorneys general stated their intention to appeal the court’s dismissal, but to date the appeal has not been filed.43Leah Nylen, “State AGs Will Appeal Loss in Facebook Case,” Politico, July 28, 2021, available at: https://www.politico.com/news/2021/07/28/states-appealfacebook-case-501247 This go-it-alone mentality may well end up burning the states in some of the other cases discussed below and lead to other prejudicial dismissals that could undermine their credibility in future antitrust cases. Given how the FTC could have benefited from additional research into areas like determining the market size for Facebook, perhaps the states would have been better off partnering with the FTC rather than filing a similar lawsuit.

Amazon

Arguably the most aggressive big tech antitrust lawsuit has been brought by the Attorney General for the District of Columbia against Amazon. The DC attorney general is not pursuing this case as part of a coalition, but instead has retained a private law firm. The suit challenges an Amazon policy which states that merchants selling on the platform cannot offer their products for lower prices or under better terms on a competing platform. While the lawsuit concedes that Amazon is not telling merchants what prices to offer, it alleges that the policy may encourage merchants to raise their prices on other platforms to avoid having problems with Amazon.

It is too early to evaluate the merits of this lawsuit; the litigation process will reveal whether this policy helps or hurts consumers. Still, there can be no dispute that Amazon’s policy has a pro-competitive rationale: Amazon wants to assure its customers that they can find the lowest prices on Amazon’s platform, or at least that they will not find lower prices elsewhere. Many companies use these types of “most favored nation” contracts, which are often deemed pro-competitive.44Michael Arin, “Most Favored or Too Favored? Suits Challenge MFN Clauses Used by Amazon and Valve,” American Bar Association, February 24, 2021, available at: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/business_law/publications/blt/2021/03/mfn-clauses/ Moreover the fact that neither federal agency nor any other state attorney general chose to join this lawsuit provides some insight into the lawsuit’s likelihood of success.

Of the recent lawsuits, more have targeted Google than any other company. It is the subject of four antitrust suits — one by the Department of Justice, with states signing on; and three led by state attorneys general. Unlike the Facebook lawsuits, these suits challenge different aspects of the company’s operations, rather than just one area of its business.

The Justice Department’s lawsuit, joined by 11 states and filed under former Attorney General Bill Barr, focuses on Google’s general search engine.2Complaint, U.S., et.al., v. Google LLC, No. 1:20-cv-03010 (D.D.C., October 20, 2020), available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1328941/download The suit contends that Google’s exclusionary agreements, where the company pays original equipment manufacturers to install Google search as the default search engine, improperly creates monopoly power and violates Section 2 of the Sherman Act.3See generally Asheesh Agarwal, “Google Gets the Scalpel, Not the Sledgehammer,” Law and Liberty, November 9, 2020, available at: https://lawliberty.org/google-gets-the-scalpel-not-the-sledgehammer/

The Justice Department’s lawsuit, joined by 11 states and filed under former Attorney General Bill Barr, focuses on Google’s general search engine.4Complaint, U.S., et.al., v. Google LLC, No. 1:20-cv-03010 (D.D.C., October 20, 2020), available at: https://www.justice.gov/opa/press-release/file/1328941/download The suit contends that Google’s exclusionary agreements, where the company pays original equipment manufacturers to install Google search as the default search engine, improperly creates monopoly power and violates Section 2 of the Sherman Act.5See generally Asheesh Agarwal, “Google Gets the Scalpel, Not the Sledgehammer,” Law and Liberty, November 9, 2020, available at: https://lawliberty.org/google-gets-the-scalpel-not-the-sledgehammer/

Another lawsuit, led by Texas, focuses on the advertising market.6Complaint, Texas, et.at. V. Google LLC (E.D.Texas, December 16, 2020), available at https://www.texasattorneygeneral.gov/sites/default/files/images/admin/2020/Press/20201216%20COMPLAINT_REDACTED.pdf The complaint argues that because the company represents both buyers and sellers, it unjustly maintains a monopoly in the market under section 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act.7See generally Asheesh Agarwal, “The New Google Suits,” Law and Liberty, January 13, 2021, available at: https://lawliberty.org/the-new-google-suits/ Google has sought to move this lawsuit from Texas to California, prompting contentious litigation and even legislative proposals in Congress.8Diane Bartz, “Judge in Texas lawsuit against Google refuses to move case to California,” Reuters, May 20, 2021, available at: https://www.reuters.com/technology/judge-texas-lawsuit-against-google-refuses-move-case-california-2021-05-20/

A third lawsuit, led by Colorado’s Democrat Attorney General and Nebraska’s Republican Attorney General, parallels the DOJ’s lawsuit.9Complaint, Colorado, et.al., v. Google LLC, No. 1:20-cv-03010 (D.D.C., December 17, 2020), available at: https://coag.gov/app/uploads/2020/12/Colorado-et-al.-v.-Google-PUBLIC-REDACTED-Complaint.pdf. This suit also focuses on the search market and Google’s payments to set its search engine as the default option.

Finally, Utah leads a coalition of 37 states and the District of Columbia that is suing Google for dominance of its app store on Android operating systems. Utah argues that the company is violating sections 1 and 2 of the Sherman Act.10Complaint, Utah, et.al., v. Google LLC, et.al., No. 3:21-CV-05227 (N.D. Cal., July 7, 2021), available at: https://1li23g1as25g1r8so11ozniw-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Utah-et-al-v.-Google-App-Store-complaint.pdf

All of these lawsuits are still in their early stages and it is far too early to evaluate their merits, particularly as they involve complex facts and markets. Still, two points are clear, even now.

First, all of the lawsuits are working overtime to define markets in a way that allows them to argue that Google has monopoly power. The search lawsuits, for example, ignore specialized search engines, such as Yelp and Amazon—more people search for products on Amazon than Google—and the ease with which consumers can switch to other search engines, such as Microsoft’s Bing or DuckDuckGo. Texas’s lawsuit excludes TV, radio, print and outdoor advertising, as well as other websites where consumers can stream videos, from its definition of the advertising market. Similarly, Utah’s app store lawsuit defines the market as “licensable” app stores—a definition that ignores Apple’s iOS system entirely, even though Apple represents the majority of users in the United States and is itself the subject of a private antitrust lawsuit.

Second, given the states’ track record, these lawsuits raise the question of whether they should have brought their cases at all. The DOJ investigated and sued Google in a complaint that, in at least some ways, was fairly aggressive. The DOJ’s lawyers and leadership had every incentive to develop a strong case, including substantial interest from the public, Congress, and the Attorney General himself. No doubt the DOJ brought every resource to bear. Nevertheless, the DOJ appears to have decided against bringing an app store case against Google and instead may be pursuing one against Apple instead.45See., e.g., Leah Nylen, “Apple Wins Round One. Round Two Will Come from Washington,” Politico, September 10, 2021, available at: https://www.politico.com/news/2021/09/10/apple-legal-washington-511261 There is also some indication the DOJ will bring a suit against Google in regards to its digital advertising business,46Eva Matthews and David Shepherdson, “U.S. DOJ Preparing to Sue Google Over Digital Ads Business,” Reuters, September 1, 2021, available at: https://www.reuters.com/technology/us-doj-preparing-sue-google-over-digital-ads-business-bloomberg-news-2021-09-01/ begging the question of why the Texas-led lawsuit didn’t join the DOJ to strengthen the case rather than retain private counsel at the taxpayers’ expense. If Google is indeed breaking antitrust laws, this method would likely have a greater chance of success.

The number, variety, and aggressiveness of the lawsuits, including those against Facebook and Amazon, raise concerns about whether law enforcement may be targeting them for reasons unrelated to consumers. Tech companies must comply with the law, but our law enforcement agencies, state and federal, must ensure that their lawsuits center on the goal of antitrust law: consumer welfare. In other parts of the world, particularly China, governments are targeting successful tech companies because of their earnings, size and independence.47See, e.g., Asheesh Agarwa, “Will the US emulate China’s tech takedown?,” The Hill, September 11, 2021, available at: https://thehill.com/opinion/technology/571821-will-the-us-emulate-chinas-tech-takedown European regulators by contrast seem to be using antitrust and the fines their laws allow them to level as a tool to punish American companies and attempt to advantage companies based in the EU.48Kati Suominen, “On the Rise Europe’s Competition Policy Challenges to Technology Companies,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October, 2020, available at: https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/201026_Suominen_On_the_Rise.pdf

It’s possible that other firms could suffer these costs to innovation and competition while going through antitrust litigation. Google, for instance, must defend multiple parts of its business from competing and conflicting claims in multiple jurisdictions at once. As the facts develop, the search lawsuit might criticize Google for allowing customers to pay to preference certain websites, even as the ad lawsuit accuses Google of denying competitors the opportunity to do the same. Facebook faces the possibility of having to unwind acquisitions almost a decade after integrating them into the company, after billions of dollars of investment. These lawsuits don’t necessarily lack merit, but their timing, number, variety and aggressiveness all raise concerns.

States and Big Tech Litigation Recap

Facebook is the first of the large technology lawsuits to be ruled on, with both the states and FTC losing the first ruling. This result should give states some hesitancy towards filing novel antitrust case theories alone.

Google is the subject of four different antitrust lawsuits that are similarly aggressive. States should be wary of their narrow market definitions that are likely to raise eyebrows in court.

The District of Columbia lawsuit against Amazon is the most aggressive and likely departs from the consumer welfare standard. It has a low likelihood of success.

Judge Posner’s Critique of State Antitrust Enforcement

With all of this recent state litigation, it is worth revisiting the views of a leading architect of modern antitrust law, Judge Richard Posner. Judge Posner served as an appellate judge for the Seventh Circuit from 1981 until his retirement in 2017, during which time he also taught at the University of Chicago School of Law. In a 2001 paper, he criticized state antitrust enforcement and recommended the repeal of federal parens patriae authority.49Richard A. Posner, Antitrust in the New Economy, 68 Antitrust Law Journal 925 (2001). As noted previously, his critique focused on the following points.

States cannot match the resources of the federal antitrust enforcers when bringing antitrust cases.

Briefs and arguments are mostly, but not always, of lower quality than those of the federal agencies.

Politics may unduly influence antitrust lawsuits.

So, how does this critique hold up?

As to Judge Posner’s first point, the states’ recent lack of success appears to support his critique. Individually and even collectively, states lack the resources, institutional expertise, and ready access to economists that the federal agencies take for granted. States can partially compensate by pooling resources in coalitions. Or, as in Texas and the District of Columbia, states can spend millions of dollars to pay private law firms to pursue antitrust cases — at their taxpayers’ expense. But their track record suggests that they are still at a significant disadvantage when they bring highly fact-intensive antitrust cases requiring sophisticated analysis.

In contrast, the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission have attorneys, economists, and support staff that specialize in antitrust analysis and enforcement. They also have a focused mission — instead of having to divide their attention among the full range of law enforcement duties, from drugs to taxes, the FTC’s Bureau of Competition and the DOJ’s Antitrust Division concentrate on antitrust law. They have been doing antitrust enforcement longer than most state attorney general offices and have specific experience in many of the industries that regularly raise antitrust concerns, including aerospace, energy, and health care.

For his second point, Posner argued that state attorneys general tend to submit lower quality briefs and arguments than federal agencies. This critique is difficult to evaluate objectively. State offices have less antitrust experience than the federal agencies, so it is entirely possible that their arguments and briefs reflect that relative lack of knowledge and expertise. Moreover, as the review of recent cases demonstrates, states tend to fare poorly in court without federal support.

Still, courts have resoundingly rejected some recent federal lawsuits, including those brought against Facebook and AT&T / Time Warner (where the states had the better argument), so it can hardly be said that the federal agencies are infallible. Neither the DOJ, FTC, nor the states have a monopoly on victory or defeat.

For his third point, Judge Posner raises a legitimate concern about state attorneys general pursuing cases based on regional or political interests. According to Posner, state attorneys general may be “too subject to influence by particular interest groups that may represent a potential antitrust defendant’s competitors. This is a particular concern when the defendant is located in one state and one of its competitors is in another, and the competitor, who is pressing his state’s attorney general to bring suit, is a major political force in that state.” Posner adds that: “A situation in which the benefits of government action are concentrated in one state and the costs in other states is a recipe for irresponsible state action.”50Richard A. Posner, Antitrust in the New Economy, 68 Antitrust Law Journal 925, at 940-941 (2001).

Major technology companies like Facebook, Google, and Amazon provide services to residents of all 50 states, as well as around the globe. But some states may be impacted differently, house major competitors of those companies, or simply have attorneys general that view the activities of a company less favorably than their counterparts. Any or all of these factors could influence a particular state’s decision to bring suit.

The recent flurry of lawsuits — within such a short period and against specific companies under scrutiny for issues unrelated to consumer welfare — suggest the possibility that politics may have played a role.

On balance, Judge Posner’s third point probably has some validity. It seems well within the realm of possibility that a state attorney general might pay more attention to an influential home state competitor, whereas all companies (presumably) have the same chances of influencing federal officials. Just as it is easier to “capture” a state legislature than the full Congress, it is probably easier to persuade any one of the 50 state attorneys general than the DOJ or FTC, particularly if a state has strong regional economic interests at stake. A state attorney general may welcome the opportunity to engage in such a high-profile lawsuit, with all of the attendant news coverage.51For example, the DC Attorney General was under consideration for a top antitrust post in the Biden Administration. Tom Sherwood, Twitter post March 17, 2021, available at: https://twitter.com/tomsherwood/status/1372261875459764224. He was not chosen, and soon after brought an aggressive case based on an unconventional theory of harm, which seems to suggest that he is calling attention to his antitrust credentials for when the next top antitrust post becomes available. As with Judge Posner’s first point, this possibility weighs against state attorneys general bringing significant antitrust cases without federal support.

The Path Forward

History should guide states as they enforce antitrust laws. In general, instead of bringing complex antitrust cases of national import on their own, states should focus their involvement in antitrust cases on instances where they have unique interests, such as local price-fixing, play a unique role, such as where they can develop evidence about how alleged anticompetitive behavior uniquely affects local markets, or where they can bring additional resources to bear on existing federal litigation.

On the other hand, states can provide a useful check on overly aggressive federal enforcement by providing courts with a traditional perspective on antitrust law—a role that could become even more important as federal agencies aggressively seek to expand their powers. Through such strategic engagement, states would best serve the interests of their consumers, constituents, and taxpayers.

There are some antitrust cases where states may have an advantage over their federal counterparts. The best examples are smaller antitrust cases where the impact is mostly in their states, and where the federal authorities choose not to act, such as local price fixing conspiracy cases. For instance, in Ohio (and no doubt elsewhere), the attorney general’s office has created a website where people can report tips on bid-rigging.52https://www.ohioattorneygeneral.gov/Legal/Antitrust/Antitrust-bid-rigging-Web-tip-form

The States as a Local Enforcer and Force Multiplier

In other instances, states may be able to develop more evidence about antitrust harms at the local level, or may care more about antitrust harms that are concentrated in their state. Pricefixing is the prime example; as a former chair of NAAG’s Multistate Antitrust Task Force puts it, price-fixing cases are the “meat and potatoes” of state antitrust enforcement.53Patricia A. Conners, “Current Trends and Issues in State Antitrust Enforcement,” Loyola Consumer Law Review, Vol. 32, No. 1 (2003), available at: https://lawecommons.luc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1267&context=lclr

In price-fixing investigations, the cases depend heavily on the facts, rather than novel theories, and resemble traditional law enforcement cases much more closely than monopolization cases brought under Section 2 of the Sherman Act. Plus, in these cases, states have at least as much of an ability as the federal agencies to develop evidence of a scheme’s effect on consumers.

For example, numerous state attorneys general are currently suing various drugmakers for fixing prices—investigations and lawsuits that fall within their wheelhouse.54See Dave Sebastian, “States Sue Drug Companies, Executives Over Alleged Price Fixing,” Wall Street Journal, June 20, 2020, available at: https://www.wsj.com/articles/states-sue-drug-companies-executives-over-alleged-price-fixing-11591823821; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-drugs-antitrust-lawsuit/u-s-statesaccuse-26-drugmakers-of-generic-drug-price-fixing-in-sweeping-lawsuit-idUSKBN23H2TR Other states, including Arizona, have been pursuing price-fixing cases involving dental suppliers pressuring dentists to purchase more expensive supplies.55See, e.g., Complaint, State of Arizona v. Benco Dental Supply, Case No. 2018-013153, Superior Court of the State of Arizona, Maricopa County, available at: https://www.azag.gov/sites/default/files/docs/press-releases/2018/complaints/Benco_Complaint_As_Filed.pdf These more conventional antitrust cases may not grab the same headlines as cases against big tech, but they are cases states can win, and when they do, they offer real economic benefits to consumers and positive headlines for those who brought them—far preferable to a loss at taxpayers’ expense.

For novel cases of national import, states should limit their involvement to supplementing federal resources. This approach seems to have worked well in the Microsoft lawsuit and other matters, such as the merger of T-Mobile and Sprint, where five states partnered successfully with the Justice Department to find a pro-consumer settlement with the firms. States have not fared well when they bring these types of novel lawsuits on their own.

Moreover, the current wave of tech cases suggests another reason to worry about overly active state antitrust enforcement. Specifically, due to the high number of states that can bring lawsuits, the states could overwhelm a company, even with little or no evidence of harm to consumers. Google is one of the largest companies in the world and can afford the compliance and legal expense of defending its business practices. This is not true of every company facing the threat of antitrust suits, however. Twitter, for example, has often been thrown in as “big tech” despite its relatively meager value compared to Facebook, Amazon and Google. Could it survive the flurry of lawsuits Google is facing now?

Lawsuits can be costly beyond a profit and loss statement. Every case presents an opportunity to lose in court, potentially forcing a restructure or major change to part of the business. Facing too many lawsuits, any company might choose to settle with the government rather than fight it out in court, regardless of the merits. Such lawsuits may show displeasure with the actions of big tech companies, but run the risk of diverting attention from innovation that would have benefited consumers.

The States as a Check Against Overly Aggressive Federal Enforcement

On the other hand, as in the AT&T and Time Warner matter, states could play a very valuable role in checking overly aggressive federal enforcement and in reminding courts of the benefits of established concepts such as the consumer welfare standard.

Broadly speaking, the antitrust winds are shifting in both the judicial and political arenas. This paper has discussed the rise of the NeoBrandeisian as a counter to the consumer welfare standard. But politicians are also considering changing the standards for how antitrust cases are decided.

For the last several decades, elected Democrats tended to be more open to antitrust cases and hostile to big companies simply because they were big and had economic power based on their sheer size. In contrast, elected Republicans tended to trust the market process, based on historical patterns that big firms that abuse their economic power don’t usually keep it for long.

Recently, however, some Republicans also have become alarmed by the size of certain technology companies, whom they view as having the power to suppress viewpoints and information. Indeed, some House Judiciary Committee Republicans have called for more aggressive enforcement of antitrust laws, particularly against Big Tech.56Ranking Member Jim Jordan, House Judiciary Committee, “The House Judiciary Republican Agenda for Taking on Big Tech,” July 6, 2021, available at: https://republicans-judiciary.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021-07-06-The-House-Judiciary-Republican-Agenda-for-Taking-on-Big-Tech.pdfThis heightened interest has led to the bipartisan coalitions of state lawsuits and legislative proposals to strengthen federal antitrust enforcement powers.

The regulatory agencies are also becoming more assertive. The FTC’s new Chair, Lina Khan, rose to prominence as a result of her Yale Law Journal paper entitled “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” a key work for the Neo-Brandesdian approach which argued for a much more activist antitrust policy toward big tech companies.57Lina M. Khan, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, 126 Yale L.J. (2016), available at: https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/ylj/vol126/iss3/3 Her approach to antitrust law appears to be generally consistent with the more activist Democratic members of Congress—much more aggressive than any recent Democrat FTC commissioners.

These ideas seek to move antitrust law away from the consumer welfare standard, which has been the standard applied by federal courts and antitrust agencies since the late 1970s, and toward more amorphous goals such as “fairness” and “democratic ideals.” In general, these ideas seek to promote competition by ensuring that markets have multiple competitors, regardless of those competitors’ ability to provide quality goods and services at low prices for consumers.

Specifically, some of the recent changes or calls for change include the following:

Democratic Senator Amy Klobachar of Minnesota proposed antitrust reform legislation that will shift the burden for companies over a certain size to prove in court that their merger will not violate the expanded antitrust laws she proposes. Among the expansions is a ban on conduct that materially disadvantages competitors or limits their opportunity to compete, which in effect is a protection for competitors even if conduct by the firm being sued is favorable for consumers.11Senator Amy Klobachar, “ Senator Klobuchar Introduces Sweeping Bill to Promote Competition and Improve Antitrust Enforcement,” Press Release (February 4, 2021), available at: https://www.klobuchar.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2021/2/senator-klobuchar-introduces-sweeping-bill-to-promote-competition-and-improveantitrust-enforcement

Republican Senator Joshua Hawley of Missouri proposed a similar bill that would ban mergers and acquisitions by companies with market capitalization exceeding $100 billion or which have been designated by the FTC as “dominant firms.” His announcement contained language very much like Senator Klobachar’s when he said it would “[r] eplace the outdated numerically-focused standard for evaluating antitrust cases, which allows giant conglomerates to escape scrutiny by focusing on shortterm considerations, with a standard emphasizing the protection of competition in the U.S.’’12Senator Joshua Hawley, “Senator Hawley Introduces The ‘Trust-Busting for the Twenty-First Century Act’: A Plan to Bust Up Anti-Competitive Big Businesses,” Press Release (April 12, 2021), available at: https://www.hawley.senate.gov/senator-hawley-introduces-trust-busting-twenty-first-century-act-plan-bust-anticompetitive-big

Republican Representative Ken Buck of Colorado and Republican Senator Mike Lee of Utah introduced the State Antitrust Enforcement Venue Act, which would provide that in most cases filed by states in federal courts, defendants would usually not be allowed to have the case moved to a different federal court. Senator Lee has been a staunch defender of traditional antitrust principles and is a former general counsel to a state governor, so it seems unlikely that he intended this bill to substantively change antitrust standards. It may have some advantages in letting state attorneys general choose the court for litigation, but at the same time it would likely prevent courts from consolidating similar antitrust claims, leading to duplicative litigation going forward in multiple courts.13State Antitrust Enforcement Venue Act of 2021, S.1787, introduced May 24, 2021, available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/1787/ titles?r=1&s=1

Not waiting for Congress to act, a majority of three FTC commissioners asserted that they can expand their enforcement power under Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act on their own authority to essentially make the FTC more of a regulatory agency than an enforcement agency. As dissenting Commissioner Noah Phillips pointed out: “Not only are [the FTC majority commissioners] refusing to articulate limits to the Commission’s ability to declare conduct illegal after investigating it, they are also refusing to articulate limits on their view of what they can regulate. Today, in effect, the majority is asserting broad authority to regulate the economy.”58U.S. Federal Trade Commission, “FTC Rescinds 2015 Policy that Limited Its Enforcement Ability Under the FTC Act,” Press release (July 1, 2021), available at: https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2021/07/ftc-rescinds-2015-policy-limited-its-enforcement-ability-under; Dissenting Statement of Commissioner Noah Joshua Phillips, available at: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1591578/phillips_remarks_regarding_withdrawal_of_ section_5_policy_statement.pdf.

The New York Assembly has taken the strongest posture toward changing the standard for antitrust enforcement away from the consumer welfare standard.59J. Mark Gidley, et.al, “New York’s Sweeping New Antitrust Bill—Requiring NY State Premerger Notification ($9.2M Filing Threshold) and Prohibiting ‘Abuse of Dominance’—Inches Closer to Becoming Law,” White and Case, June 11, 2021, available at: https://www.whitecase.com/publications/alert/new-yorks-sweepingnew-antitrust-bill-requiring-ny-state-premerger-notification The “TwentyFirst Century Anti-Trust Act” would change the standard from consumer welfare to the European model of “abuse of dominance.” This standard would be defined as “It shall be unlawful: (a) for any person or persons to monopolize or monopsonize, or attempt to monopolize or monopsonize, or combine or conspire with any other person or persons to monopolize or monopsonize any business, trade or commerce or the furnishing of any service in this state; (b) for any person or persons with a dominant position in the conduct of any business, trade or commerce, in any labor market, or in the furnishing of any service in this state to abuse that dominant position.” The bill would also presume a company would be in a dominant position if it had greater than 40% market share as a seller or 30% as a buyer. This wouldn’t be the only change. The bill would require a premerger notification threshold of $9.2 million if the business had a qualifying presence in the state, making New York only one of three states with such a requirement. It would also allow for class action lawsuits to seek treble damages, increasing the likelihood of such cases.60New York State Assembly, “Twenty-First Century Anti-Trust Act,” Bill No. S00933A, introduced January 6, 2021, available at: https://nyassembly.gov/leg/?default_fld=&leg_video=&bn=S00933&term=&Summary=Y&Text=Y

This recent trend raises concerns about what standard will be used for evaluating antitrust claims brought by states. Given heightened interest at the federal level in moving from consumer welfare to an unspecified standard that would target big technology companies, we can anticipate that some states will soon follow along. Indeed, the District of Columbia case against Amazon does not appear to be based on consumer welfare standards.

So far the federal courts have not endorsed this movement away from the consumer welfare standard, and Judge Boasburg’s recent ruling in the FTC and states’ cases against Facebook suggest that courts may not cooperate with this interest in changing antitrust standards. Nonetheless, there are several paths for aggressive enforcers to change the standards, whether through new federal legislation, a successful assertion of new enforcement power by the current FTC majority, or by state judges allowing for new standards.

Moreover, enforcement under state antitrust laws, such as the case brought by the District of Columbia against Amazon, may not be so bound to the consumer welfare standard. If the TwentyFirst Century Anti-Trust Act becomes law, it could have massive implications for the future of antitrust law and the economy. New York’s different standard and economic importance would open dozens of companies to different antitrust scrutiny than the rest of the nation.

New York could become the de facto antitrust enforcer for the states, or other states would likely follow suit and change their standard. Moving from the consumer welfare standard to something more arbitrary could be a huge blow for the role of economic analysis in American antitrust.

Given all of these potential changes in state and federal law, state attorneys general could play a critical role in the next few years in defending established concepts like the consumer welfare standard and countering federal attempts to expand their power, such as the FTC’s possible rulemaking to ban non-compete clauses and exclusive contracts, both traditionally the province of state law. States can also continue, and perhaps even step up, their core pricefixing enforcement and bringing cases that involve measurable harm to consumers. These cases affect everyday consumers in meaningful ways, in contrast to higher profile cases with very low likelihood of bringing benefits to consumers even if a state can win the case in court.

Attorneys General Should Consider the Following Antitrust Actions

Pursue cases where they have unique advantages and interest such as local price fixing

Push back against overly aggressive antitrust enforcement, especially from federal agencies that harms consumers

Avoid cases where they go it alone, especially when trying novel antitrust theories.

Conclusion

States should exercise caution when considering antitrust cases that have strong implications outside of their borders. They should recognize the difficulty in proving complicated and fact-intensive cases. Instead of bringing novel, complex antitrust cases of national import on their own, states should focus their involvement in antitrust cases on instances where they have unique interests, such as local price-fixing, play a unique role, such as where they can develop evidence about how alleged anticompetitive behavior uniquely affects local markets; or where they can bring additional resources to bear on existing federal litigation. On the other hand, states can provide a useful check on overly aggressive federal enforcement by providing courts with a traditional perspective on antitrust law — a role that could become even more important as federal agencies aggressively seek to expand their powers. Through such strategic engagement, states would best serve the interests of their consumers, constituents, and taxpayers.

About the Authors

Eric Peterson is the Director at the Pelican Center for Technology and Innovation at the Pelican Institute in Louisiana. He has previously worked at the Institute for Free Speech and Americans for Prosperity focusing on the intersection between technology and free speech

Ted Bolema is Executive Director of the Institute for the Study of Economic Growth and Associate Professor of Economics at the W. Frank Barton School of Business Administration at Wichita State University. Bolema previously was a Senior Fellow with the Free State Foundation, a think tank specializing in telecommunications policy, and Director of Policy Research Editing at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. He also served as a trial attorney with the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, as a Special Assistant U.S. Attorney with the Eastern District of Virginia, as an antitrust attorney with Weil, Gotshal and Manges in New York City, and as an adjunct professor at the Antonin Scalia Law School at George Mason University

Appendix 1

Appendix 2